The legacies of Joe Paterno and Sean Payton, though marked by very different trajectories, both underscore a powerful phenomenon in sports: the “coach as emperor” model. These coaches wielded influence that extended well beyond the game, transforming them into figures of monumental authority within their organizations. While Paterno’s tenure at Penn State exemplified the unchecked control often found in college sports, Sean Payton’s time with the New Orleans Saints highlighted how professional sports are not immune to this dynamic. This article delves into how Joe Paterno and Sean Payton represent two sides of the same coin—one in college football, the other in the NFL—each revealing the impact and risks of coaches granted significant autonomy.

Joe Paterno’s Rise to Power at Penn State

Joe Paterno’s legendary career at Penn State began in 1950 as an assistant coach, eventually culminating in his promotion to head coach in 1966. Over decades of success, Paterno became synonymous with Penn State football, accruing not only wins but also a level of influence that permeated every corner of the university. Paterno was more than just a coach; he was an institution. Known for his commitment to “Success with Honor,” he shaped the university’s identity and culture, transcending his role on the sidelines. This immense influence allowed Paterno to operate with minimal oversight, setting a precedent for the “coach as emperor” model. His unchecked power and the reverence he inspired among players, fans, and administrators ultimately contributed to his downfall, highlighting the risks inherent in this model.

The Freeh Report and the Extent of Joe Paterno’s Influence

The release of the Freeh Report in 2012 revealed just how deep Joe Paterno’s influence at Penn State ran. According to the report, university administrators deferred to Paterno on numerous decisions, allowing him to exert unprecedented control over the program and beyond. Even the Board of Trustees, which was supposed to provide oversight, found itself bypassed by administrators who were reluctant to question Paterno’s authority. This lack of accountability facilitated a culture where Paterno’s decisions went largely unchecked, eventually culminating in one of the most significant scandals in college sports history. The Freeh Report underscored how power structures in college sports often enable influential figures like Paterno to act autonomously, shedding light on the dangers of the “coach as emperor” phenomenon.

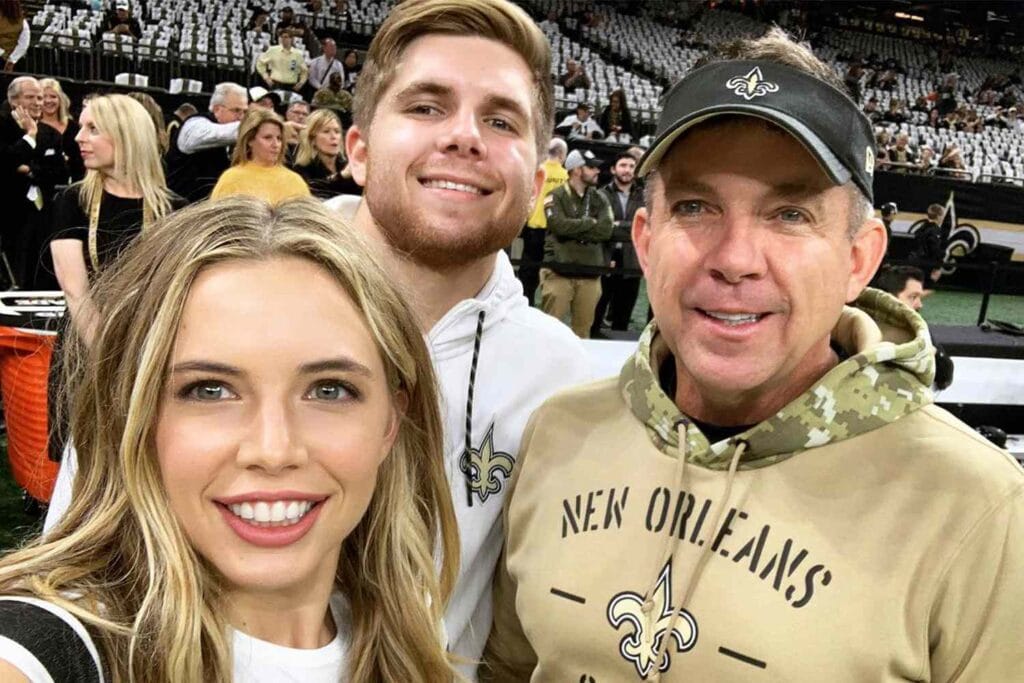

Sean Payton and the “Coach as King” Mentality in the NFL

While Joe Paterno embodied the “coach as emperor” dynamic in college sports, Sean Payton exemplified it in the NFL. Payton, who spent over 15 seasons with the New Orleans Saints, gained a level of influence that few NFL coaches attain. His success in leading the Saints to a Super Bowl victory and consistently competitive seasons earned him the trust and admiration of fans, players, and even ownership. However, this level of authority led to a situation where Payton began to operate with relative autonomy, famously disregarding directives from both the Saints’ ownership and the NFL Commissioner’s Office during the “Bountygate” scandal. In this scheme, players were allegedly incentivized with cash bonuses to injure opposing players, violating league rules. Payton’s involvement, and subsequent suspension, highlighted how unchecked power can foster an environment where ethical lines are blurred, if not outright ignored.

The Parallel Paths of Joe Paterno and Sean Payton

Despite their different settings, both Joe Paterno and Sean Payton represent the risks associated with the “coach as emperor” model in sports. Paterno’s influence was rooted in decades of success, tradition, and loyalty at Penn State, while Payton’s authority was built on his Super Bowl victory and his reputation as an offensive genius in the NFL. Both coaches held significant sway over their organizations, and both faced significant scandals that revealed the dangers of operating with limited oversight. These cases demonstrate how success, loyalty, and a favorable public image can create an environment where coaches feel emboldened to act independently of organizational rules or ethical considerations.

The Concept of “Costly Information” and Sports Governance

One of the reasons both Joe Paterno and Sean Payton were able to maintain such high levels of control within their respective organizations was due to what economists refer to as “costly information.” This concept explains the difficulty and expense associated with gathering accurate information to monitor the behavior of influential figures, especially in complex organizations like sports teams. For Penn State, monitoring Paterno’s actions would have required administrators to challenge a figure revered by fans and alumni, a task that few were willing to undertake. Similarly, in the NFL, the Saints’ ownership likely found it difficult to counter Payton’s decisions, given his success and the deference he commanded. This costly information problem allowed both coaches to operate with a degree of independence that ultimately led to their downfalls.

Player and Fan Loyalty: A Shield of Influence

Both Joe Paterno and Sean Payton benefited from immense loyalty from players, fans, and the media, which only strengthened their positions of power. For Paterno, the loyalty of former players and the devotion of the Penn State community created a protective shield that made it difficult for administrators to question his actions. Similarly, Sean Payton’s success with the Saints endeared him to New Orleans fans, players, and local media, allowing him to operate with a level of autonomy unusual in professional sports. This loyalty not only shields influential figures from scrutiny but also enables them to maintain control over their organizations, often at the expense of accountability.

How Recent Drafts and Recruits Compare to the Paterno and Payton Legacy

Since Joe Paterno’s era, college football has seen many new coaches emerge, while the NFL has welcomed younger, innovative minds. However, few recent hires or players have reached the level of control and influence seen with figures like Paterno and Payton. Governance structures in both college sports and the NFL have evolved, aiming to prevent a single figure from wielding such disproportionate power. This shift, while essential, has also transformed the dynamics between coaches, players, and administrators. Coaches today are less likely to be granted unchecked control, which limits their ability to shape organizations in the same way Paterno and Payton once did.

Comparing the “Coach as Emperor” Model in the Post-Paterno and Payton Era

While the influence of figures like Joe Paterno and Sean Payton remains unmatched, the current sports landscape has evolved to incorporate more checks and balances. In the NFL, coaches like Bill Belichick of the New England Patriots still wield significant authority, but under a stricter framework of oversight. In college football, coaches like Nick Saban at Alabama command immense influence, yet university boards and athletic directors are more vigilant in monitoring their activities. The lessons from Paterno’s reign at Penn State and Payton’s time with the Saints have reshaped governance in sports, prompting administrators to prioritize accountability without compromising the competitive edge these coaches bring to their teams.

Lessons for Future Governance: The Legacy of Joe Paterno and Sean Payton

The legacies of Joe Paterno and Sean Payton offer critical insights for the future of sports governance. While their influence brought success, it also exposed the dangers of unchecked power within sports organizations. Moving forward, both college and professional sports must balance the need for strong leadership with the importance of accountability. From Paterno and Payton’s cases, administrators, team owners, and governing bodies can learn to create governance structures that allow coaches to excel without overstepping ethical boundaries.

Joe Paterno, Sean Payton, and the Future of Sports Leadership

The careers of Joe Paterno and Sean Payton illustrate both the potential and the pitfalls of the “coach as emperor” model in sports. These coaches, though vastly different in their approaches and settings, highlight the challenges of balancing influence with oversight in competitive environments. Joe Paterno’s legacy at Penn State and Sean Payton’s impact on the New Orleans Saints are reminders that unchecked power, while capable of delivering success, can also lead to ethical lapses and organizational crises. As the sports world continues to evolve, the influence of these figures will shape discussions on governance, ethics, and leadership for years to come. Their stories call for balanced leadership structures that allow for excellence without sacrificing accountability.